For older student to adult English-speakers who want to be able to learn French through English, you will need to take the time to learn French grammar.

You probably don’t want to hear this, but brushing up on your English grammar first will help you get the basic concepts of grammar in French down better and more quickly.

There are a few quirks, but fortunately French grammar rules don’t differ from English in any truly dramatic ways. For example, here is what is the same between English and French:

- In French simple sentence is still in subject-verb–object order (subject of the sentence followed by the action, followed by what the action is done to, if any).

- French uses articles before nouns (the/a) just like English does.

- You can ask questions using the inverted verb-subject order, though just like in English, you can also raise your pitch at the end of a sentence to indicate a question as well.

- All the basic sentence elements, including adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, exclamations, exist in French in much the same way they do in English.

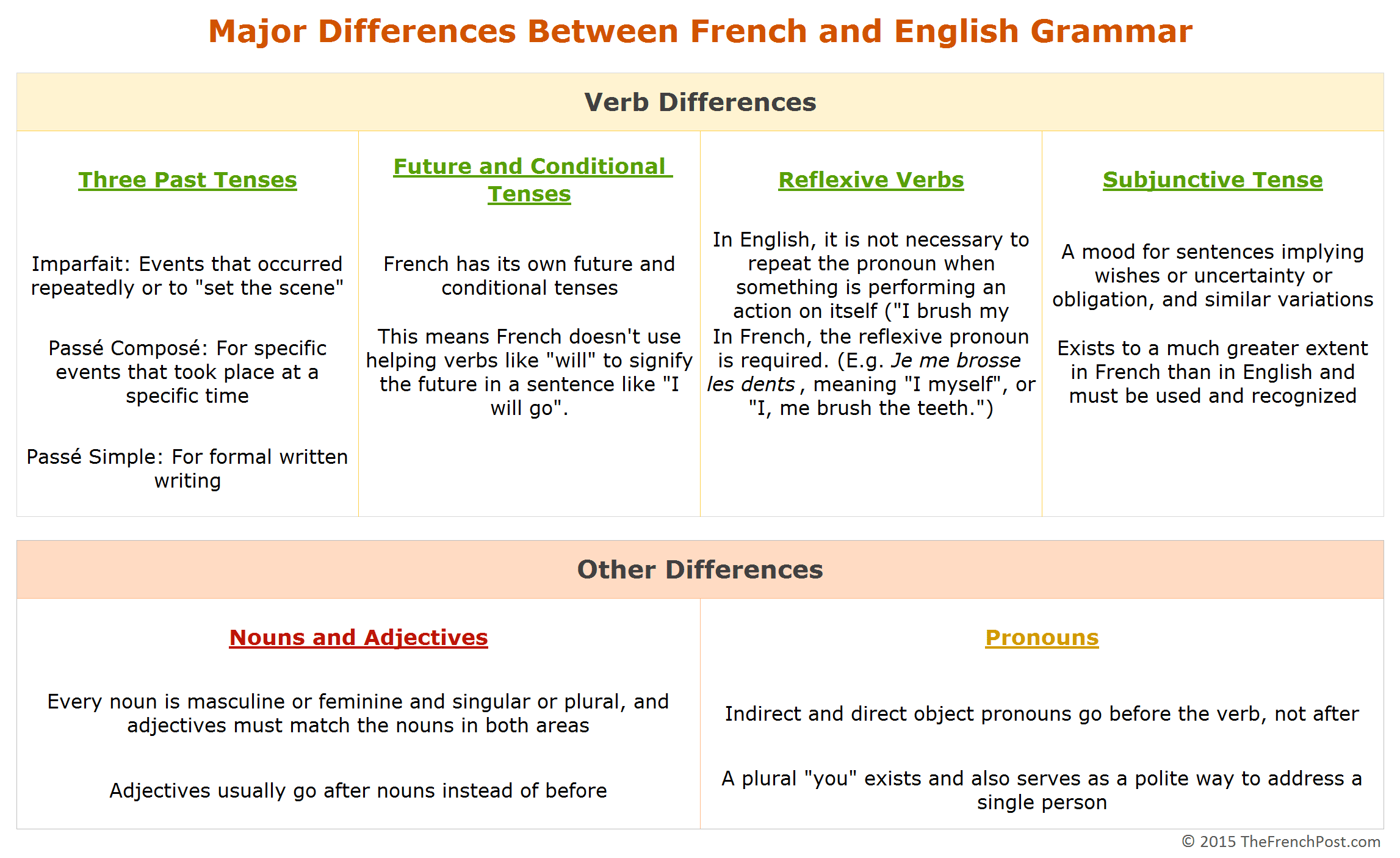

However, there are the important differences in French grammar compared to English grammar that you should be aware of. Here is an overview of the most important distinctions:

More Differences and Details

Below are more details on the differences between the two languages, along with some clarifications.

Nouns and Adjectives

Adjective-noun order: Adjectives (usually) go after the noun, not before. So, it’s a green car in English, but une voiture verte in French. The only exception is a handful of very common adjectives, such as bon, nouveau, and grand.

Noun gender: In French, all nouns are either masculine or feminine and either singular or plural. This alters the adjectives and articles that describe them. As in the example above, voiture is feminine, so it gets the feminine indefinite article (une instead of un) and the feminine version of vert, verte. If you were describing deux (“two”) voitures, the adjectives would be bonnes or vertes or grandes.

Verbs

Future and conditional verb tenses: French has distinct conjugations for many verb tenses, including the future and conditional tenses. This means that where you would say “will + verb” or “would + verb” as in English (such as “I would leave” or “They will call”) to indicate that an action will be performed in the future or on a conditional basis, in French every verb has its own future and conditional forms.

- For example j’irai is “I will go”, which is future tense, and j’irais is “I would go”, which is the conditional tense. Luckily, the verb forms are usually regular and easy to memorize.

Verb tenses that don’t (or barely) exist in English: The two biggest verb tense differences are 1) addressing the two types of basic past tense (passé composé and the imparfait), and 2) the subjunctive mood. The sentence characteristics to recognize to help you decide whether to use passé composé versus the imparfait tense are fairly easily learned and straightforward. As a general rule, passé composé is used for specific, singular actions that occurred in the past, while imparfait is for mood setting and on-going actions. You probably won’t get it right 100% of the time, but you can get to about 90-95% accuracy with practice.

The subjonctif is something French teachers will tell you is a mood and not a tense, but since it has its own conjugation rules, the difference is essentially an academic exercise. You definitely need to recognize it, but you can get away without using the subjunctive tense yourself to an extent. We would suggest sidestepping it for now and coming back to it when you have the major other verbs down. You can’t avoid using the subjunctive forever, as there are certain sentence structures that require the subjunctive and you won’t want to be limited in your ability to communicate, but it can be delayed for a while.

Pronouns

Indirect and direct object pronouns: Do you remember direct objects and indirect objects from grammar lessons in school? Take a sentence like

“I brought the books [direct object] to my friend [indirect object].”

This sentence, when translated to French, is in exactly the same order.

“J’ai apporté les livres [direct object] à mon ami [indirect object].”

All is well, and shouldn’t even have to think about direct objects versus indirect objects. The difference comes in when you use pronouns to replace the direct and indirect nouns– e.g.,

“I took them to him.”

In that instance, the two pronouns that replace “the books” and “my friend” actually go before the verb.

So the sentence would be, “Je les lui ai apporté”.

Not exactly an instinctive structure for an English speaker, but definitely learnable!

The plural “you”: In English, there are regional variations of “you” to indicate the speaker is addressing more than one person – for example, “y’all” and “you guys”, among many others. These phrases exist because English doesn’t have two different words to specify whether the “you” is one person or many. That problem is solved in French! There’s tu for addressing a single person, and vous for addressing more than one (and also used instead of tu toward a single person to show politeness).

What’s Next?

Hopefully none of this scared you off learning French entirely. Like any other language, you’ll take it one lesson at a time. If you get overwhelmed at any point you can just keep reading and practicing the parts you already know until you’re comfortable moving forward again.

If you still need some direction on where to start, learn more about beginning French here. If you’re ready to start learning some French, the best place to start is probably with the same grammar topic that almost all textbooks do: the present tense! Have fun!